Episode #71: Donna Griffit world-renowned corporate storyteller

In this episode, we’re excited to be joined by Donna Griffit, a world-renowned... Read more

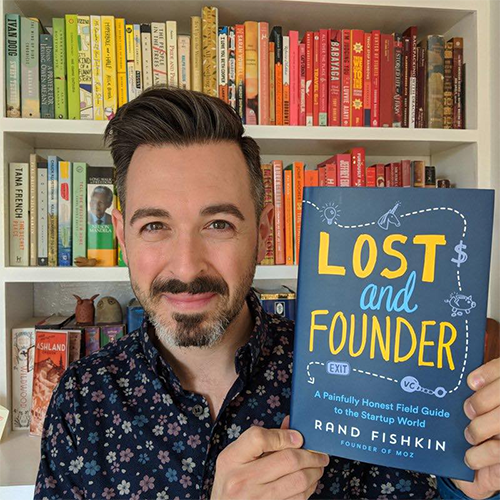

In this episode of the RealLifeSuperPowers podcast, we speak with SEO genius, author and serial entrepreneur Rand Fishkin. Rand built MOZ a 45 million dollar a year venture that’s a b2b software for marketers helping companies rank well in Google. He’s recently founded a new company called SparkToro. He’s also published a new book called Lost and Founder, which is basically a cheat roadmap for entrepreneurs. It’s PACKED with experience based tips on what actually works without BS. It’s egoless and transparent at almost unbelievable levels, and as you’ll hear, such is Rand.

We discuss:

The irony of founding a company that makes millions in revenue but not being able to become rich due the complexity of being venture backed

How so called “lifestyle businesses” are underestimated and essentially only one path is marketed to entrepreneurs, making it appear as if there’s only one choice – to be venture backed “all of the attention and all of the accolades go to a handful of companies that grow fast and have big exits and big fundraising events. You never read in the newspaper in the tech press about a company that makes 2M dollars and 500K of that is profit for its owners, even though that’s a great story that’s wonderful for the founders, that’s never talked about, never read about, reporters don’t investigate. BUT someone raises 2M dollars – that story is everywhere even though 90% of venture outcomes don’t return enough money to be considered a success for the fund”.

The complexity of working with family.

The risks of becoming overconfident and turning down acquisition offers under the assumption that you can do better. “In this world where dollars are chasing, not dollars, not profitable businesses, not sort of good survivable businesses but growth and growth alone, you should recognize that even at small revenue numbers, having a high growth rate is potentially your most exciting asset. And when you have a very high growth rate, even when you’re small, that might be a great time to market and sell your business”

The power of vulnerability.

And so much more..

We hope you enjoy this and learn from him as much as we did!

Zooming out, if you like listening to this podcast, make sure to subscribe so you don’t miss new conversations with peak performers, serving as a reminder we can all tap into the best versions of ourselves.

You’re also welcome to follow Ronen and Noa on Linkedin

And if we may ask for a favor – please leave us a review on your native podcast app.

Some further resources:

Noa Eshed 0:00

In this episode we interview SEO genius author and serial entrepreneur, Rand Fishkin. Rand built Moz a $45 million a year venture. That’s a B2B software for marketers helping companies rank well in Google. His recently founded a new company called SparkToro. He’s also published a new book called Lost and Founder, which is basically a cheat roadmap for entrepreneurs. It’s packed with experience based tips and what actually worked without BS. It’s egoless and transparent at almost unbelievable levels. And as you’ll hear, such as Rand. We hope you enjoy this and learn from him as much as we did.

Noa Eshed 0:56

So hey, we’re here with Rand Fishkin. How are you, Rand?

Rand 0:59

Very well, thank you for having me.

Noa Eshed 1:01

Great, of course. So recently, read your new book, Lost and Founder, which we really recommend to anybody, both employees and entrepreneurs. And like, the first thing that jumps to mind is that where do you get the courage to be so transparent? In a world of such ego and startups, you’re being so open about everything?

Rand 1:20

Yeah. I mean, for me, it’s much less of a choice. I think it’s something that I feel passionately about. And I really hate the the idea of secrecy, I hate when you know, stories are told that aren’t true. And when messages are amplified, that aren’t the whole story that aren’t accurate. And so for me, transparency is a way of, I guess, fighting back against that.

Noa Eshed 1:45

Do you feel like you’re getting feedback from the startup community about the book? Are people getting a bit annoyed that they’re sort of bursting a bubble?

Rand 1:54

I would say 95% of the feedback is very positive. But yeah, there are a few people. I think, particularly, you know, obviously, if you read the book, right, so I don’t think folks in the venture community aren’t particularly thrilled with it.

Ronen 2:08

But you definitely gave me inspiration now. So I’m going to do this. I’m getting the courage. I sold a company a few years back to publicly traded company and I’m driving a Kia Sportage. So I just have to say that myself, like I know, I feel the inspiration. So I just have to tell our listeners that…

Rand 2:29

That is awesome to hear. And hey, there’s nothing wrong with driving a Kia. Geraldine and I had a Kia for what 12 – 13 years? It was awesome.

Noa Eshed 2:38

You don’t own your Kia right now?

Rand 2:41

No, no. unfortunately it died. No longer functions, but it served us well for more than a decade.

Noa Eshed 2:48

What do you drive now?

Rand 2:49

We have a Ford Hybrid.

Noa Eshed 2:51

Got it. Will, burst the bubble.

Ronen 2:54

I feel alone with the Kia now though. I feel ashamed. It was too soon…

Rand 2:58

No, anyone who defines himself by the car they drive, ooff, you’re hanging out with the wrong people.

Noa Eshed 3:04

That is so true. And so let’s take a bit of a step back, just for the people who know you mostly as the SEO genius from Moz. So maybe tell us a bit about how Moz evolved, like how did you get that from zero to the empire that you’ve built?

Rand 3:24

Empire? Well, I’m not sure I would describe it quite that way. But we Moz initially started as a consulting business, you know, I had well, even before that is just a blog, right? I was learning SEO, I was a web designer. And I found the practice of SEO very frustrating to learn, I found a lot of conflicting and inaccurate information. I was extremely frustrated by the search engines hiding all the information about what they had built and how they they worked and operated. And so I created this blog to hopefully help break through some of the noise about that and share my journey as I was learning the process. And it was, you know, it was not a great blog, I think it took a couple of years before it got any serious traffic. But when it did, it turned into a great machine for generating consulting leads. And so we sort of switched our business from web design to SEO. And that’s when when SEO Moz was born as a as a business rather than just a blog. And then we were doing reasonably well as consultants for a few years, mostly on the success of the blog and getting invitations to speak at conferences and events, which which all came through the blog and then that consulting business turned into a software business because we had built some tools behind the scenes and you know me I don’t like to keep things hidden or secret. So I wanted to make all our tools transparent and available to anyone, but we we couldn’t afford to make them free. So we had to set up a little PayPal paywall and that’s ended up generating so much revenue in the first six months that we realized we had, you know a business that was as big and potentially a lot bigger than our consulting business. And so over the next couple of years, we shut down the consulting business, I raised some money from venture capital firm here in Seattle called Ignition Partners and became sort of officially CEO of the, of the new software company. And over the next seven years, yeah, we went from, you know, a couple $100,000 in software revenue to gosh, I think it was about $30 million, when I stepped down as CEO, and, and promoted my longtime chief operating officer to the role. And then I spent the next four years at Moz, as kind of an individual contributor and board member, stayed on the executive team for a long time and then left the company in February, I think, you know, this year Moz will do maybe in the around $57 million in revenue. So it’s, you know, it’s, it’s a good company in a lot of ways. I think it’s helped a lot of people. And that’s what I feel really good about, but it, you know, because it’s venture backed, it’s kind of this stuck in the middle business where it’s not growing quite fast enough to, you know, make the stock liquid, it’s, you know, it’s gonna have a tough time sort of getting to IPO unless the growth rate gets up.

Noa Eshed 6:17

And this is because it’s venture backed?

Rand 6:19

Yeah, just the complexities of the venture model mean that, that while Moz is doing well, it’s sort of not really doing well enough to be considered a success in that in that frame of mind.

Noa Eshed 6:32

So what would it be considered a success? Because it sounds like it’s doing very well.

Rand 6:37

Well, so let’s see, Moz is growing at about maybe 10 – 11%, year over year, I think, I think the minimum bar for venture sort of successful companies would be maybe 25, but probably more like 30% year over year growth, growth in terms of revenue growth, and Moses profitable, which is unusual for venture backed companies, and generally not preferred, you know, I think that most venture firms prefer that you are, are burning capital or running very close to break even, but you’re spending lots of dollars to grow faster, the model doesn’t really encourage or support a – hey, we’re, we’re a profitable company that’s spitting off dollars, it’s designed to grow as fast as possible to be as attractive as possible for either an IPO or an acquisition. And those outcomes are dependent on growth rate, much more so than profitability.

Ronen 7:30

That’s a really interesting subject, because a lot of people aren’t looking at exit strategies. And it’s funny to say that profit is not one of the most common exit strategies.

Rand 7:41

Which is, it’s dumb, just dumb.

Ronen 7:43

It’s not only dumb, it’s like, if you tell me the first day, when I got into business, saying – listen, you don’t want a company to be profitable, you want it to grow, you want to have burn rate, you want to have a lot of backing behind it. Like, I wouldn’t get the logic. It’s like the logic of cash flow, which is also illogical. So the more you grow, and the more you the better you do, the better worse cash flow. So in that strategy, if you’re finding a space like that, what do you do, because I hear you kind of apologizing right now for having a profitable $57 million revenue company, which is not for an IPO and exit, but it’s a fantastic company, which is actually a lot safer than most of the, you know, other startups or tech companies out there. So they, what do you think about that in your perspective,

Rand 8:31

I think that this model is, I think that at the core the model is broken, right? It’s essentially, it’s essentially a tax dodge vehicle, right. The reason that growth is preferred over profits is because investors and owners of stock get taxed at lower rates than people who earn profits from their business that they own or people who are employees. And so, you know, essentially, in order to save whatever, you know, in the United States, somewhere between 20 and 30%, on their tax rate, the entire sort of capitalist system, ecosystem of wealthy dollars has gone into trying to find fast growing high price exiting companies, and assets rather than profitable businesses or businesses that pay a lot of money to, to them to work there, those kinds of things. So it’s a it’s a very odd model, but I think a natural result of sort of, you know, when when the tax code is structured in a certain way incentives change, and that’s, that’s what causes these businesses to do these odd things. And I think that’s why it doesn’t make logical sense.

Noa Eshed 9:42

How can a starting entrepreneur sort of win this game?

Rand 9:46

I mean you have to decide for yourself, right? You decide, as an entrepreneur, you you say – look, I am signing up to play the game, right? And you get us to choose you say – I want to build a long term profitable business that pays its staff and employees well, and these kinds of things, or, you know what, I think I’m up for the capital gains tax rate optimization model of growth at all costs, you know, raising institutional capital and seeking to get a 5 to 10x return on that money in seven years or less, you know, 7 to 10 years, those kinds of things. So it’s a choice, is a choice that we all make, I think that one of the biggest problems in the field is that entrepreneurs don’t feel like they have a choice. They feel like only one model is marketed to them. And I think they’re right, right, that, that all of the attention, and all of the accolades go to, you know, a handful of companies that grow fast and have big exits and big fundraising events, you know. You never read in the newspaper, or, you know, in the tech press, right, you never read company, you know, makes $2,000,000 and 500,000 of that is profit for its owners, right, even though that’s a great story. That’s wonderful and awesome for those people who built that business that is never talked about, never read about, reporters don’t investigate, but someone raises $2 million. That story is everywhere.

Noa Eshed 11:19

Even though that may lead to nothing.

Rand 11:20

Even. And most of the time, that is exactly what it leads to, right. I think about 90% of venture outcomes don’t return enough money to be considered a success for the fund. Right? So

Noa Eshed 11:30

Yes, success is celebrated very early in these scenes.

Rand 11:33

Yeah. And I think that’s part of it, right? That consciously or unconsciously, to the you know, to an individual investor, the way the market is set up is to advertise to entrepreneurs, that the the only real path is, you know, a venture backed or an institutionally backed path. And that’s not to say it’s a bad one, I think that it can be remarkable and wonderful for some people. You know, if you’re, if you’re one of the 1 in 10, it’s pretty awesome. Can be anyway, and, and that’s great. But the problem is that I don’t think the alternatives are presented.

Ronen 12:08

1 in 10?

Rand 12:09

That’s, I mean, it depends on which statistics you look at, right? So I think, I think maybe six or 7% of venture investments would be considered successful by the investor and maybe a little bit more would be considered successful by the entrepreneur, because there’s, there’s a healthy number of aqua hires and sort of small exits where the entrepreneurs still feel okay. I think a big challenge, a bigger challenge is talking about employees in this field, where I think it’s more like 3 and 100, that where the teams make enough money from their stock and stock options, or acquisition bonuses to be, you know, to have said – wow, I think we did better in this company that I this startup that I joined than I would have done if I had gotten a job at Google or Microsoft or Amazon or Facebook or something like that.

Ronen 13:02

Right.

Noa Eshed 13:03

And that’s something also that you discuss in your book, not, not specifically the the cost and the value for the employees, but it’s part of what you discuss about a cultural fit. Because I think maybe once people are not driven precisely by money, then maybe that has more potential for the business as well, then maybe then people are driven by other motive.

Rand 13:24

Yeah. And I think that that’s one of the things that’s really tough about, about the binary aspect of this model, as well, which is that I think, many entrepreneurs want to build a business because they’re excited about the potential of that business existing, you know, and making, making a difference in the world, whatever, whatever world they happen to be in, or whatever world they’re excited about. And I know, tons and tons of entrepreneurs who, you know, when we meet when we talk about what they’re building and what they want to do, or people who are trying to get jobs and what they want to do, we unfortunately end up talking about how can they successfully pitch and raise money? Right? How can they sell an investor on the idea that their their company is interesting, rather than how can they make the company live and survive and thrive.

Noa Eshed 14:15

Do you think if they talked about that, that would make a difference? I mean, at the end of the day, they need the funds, so if they don’t have that, then it’s just a bunch of people with a hobby, isn’t it?

Rand 14:24

So I think this is an interesting case where many businesses can start and grow without significant investment, and certainly without institutional investment, right venture or private equity or, you know, asset classes like those making the investment. And, and yet many people believe that they can’t do it without, you know, without that first round of venture and believe that there’s and structure their business in a way that requires it demands it. I don’t think that’s a good good move either. I think if you’re designing a business, in the early stages, you don’t know whether it’s going to be a good fit for, you know, venture or, or private equity or, you know, angel investors or bootstrapping or whatever, right? You, you just don’t know. And so doing those first few months or even years of investment, whether that’s in your side time or, you know, bootstrap yourself or with a little bit of angel money, I think is a really smart way to go before you go try and raise these huge rounds from these institutional investors who have much bigger exit expectations.

Noa Eshed 15:37

Yeah, and would also lose interest in you very quickly if your growth rate isn’t what you’ve described before.

Rand 15:42

Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

Noa Eshed 15:45

And then just going back, rewinding back a little bit, so how did you end up getting interested in SEO in the first place and you started working with your mom? Like, how did you end up working with your mom? It’s not very standard.

Rand 15:59

No, no, I don’t think I think mom and son business is probably one of the least likely combinations in the field. So I had done a little bit of contract design work for my mom’s, you know, marketing consultancy business in the late 90s. And when I dropped out of college in 2001, I told my mom – hey, I want to work with you full time and just do web design. And I think there’s a big market here. And she said – sure. And then of course, the .com crash happened. And we we sort of panicked for a few years and went deeply into debt and tried to figure it out. But then I think that the more in debt, we got, the worst things went, the more we were stuck together, trying to figure out how to make this business survive. And we had, we had some good years, we had some tough years.

Noa Eshed 16:46

Was she in Moz, all throughout the years or did she leave at some stage?

Rand 16:51

Yeah, let’s see. So she, she was the president of the company until 2007. And that’s when, you know, when we raised venture, they basically said – Hey, Rand, you know, we want you to be CEO. And so that was a that was kind of a tough conversation between the two of us.

Noa Eshed 17:06

How did she take it?

Rand 17:07

Um, I think, you know, like I said, I think it was hard. I think it was emotionally hard. And, you know, she felt like – hey, this is a company that I, you know, built since 1981. Right. So to have somebody else, kind of take it over, I think she was proud of me and excited for whether business could go but also, yeah, it’s sort of sad and frustrating, and probably a lot of emotions that I think were probably hard to process at the time.

Noa Eshed 17:32

Yeah. And did you feel like you got stronger your relationship out of it? Or did he maybe sort of make it take a step back from each other?

Rand 17:40

Yeah, I would say that probably the latter of those two, it was it was just, I think it was hard on hard on her. And I, I felt probably still feel guilty about it. Right. And, you know, I’m not sure I’m not sure that at the time and going forward the next few years, you know, my mom didn’t have the best sort of working relationship with some of our board members and some of the team at Moz, which a lot of what, you know, a lot of them I had hired and brought in so yeah, I think that was I think it was really hard. And I certainly feel for her because later in my career, sort of a similarish thing happened to me, I think more more voluntary on my side, but…

Noa Eshed 18:24

When you stepped down from being CEO?

Rand 18:25

Yeah, when I stepped down from being CEO, I think I had an expectation of how the working relationship would develop over the, you know, over the years to come, I wanted to stay at Moz for a long time for the for, at least until Moz sold. And of course, the company’s growth rate up until 2014, right, the year that I stepped down with, had been very high, you know, 100% year over year for six years, and then I think, you know, slowing to 50 55%, the last year, but after that it slowed dramatically, you know, it went went down to maybe 20%. And, you know, the last few years, it’s been 10%. So, it kind of went from a company that, you know, everybody was excited about and lots of investors were excited about the stock was worth a lot of money. And that actually to answer your earlier question. So my mom managed to sell some of her stock in what was that, 2013, 2012 or 13. She sold a good chunk of it and made a nice bit of money, something I, I regret doing, I should have, should have joined her, but I was sort of very overconfident that that it was going to be worth even more in the future.

Noa Eshed 19:30

And I think that’s a big lesson that followed you through other decisions that you’ve made, including, for example, turning down a huge offer of investment from HubSpot, right from Brian Halligan, who was also a guest on the show.

Rand 19:44

Yeah. So not an offer of investment. They offered to buy the company. You know, they’re basically they said – hey, we want to we want you know, HubSpot to buy Moz and I was excited about that, but I was again greedy and overconfident thought thought we’d be worth even more in a few years. And I clearly should have said yes to that for a number of reasons. But even even if we’re purely talking about the financial side, you know, HubSpot would have almost certainly paid a lot of that in stock rather than cash. And you know, of course, HubSpot’s stock in 2015, when they went public was worth 20 times 30 times what it was worth in, in 2011, when we would have gotten it. So, oops.

Noa Eshed 20:25

That must come up in like, family dinners.

Rand 20:28

Yeah, it comes up comes up of it.

Ronen 20:30

But you’re saying that also like, that’s a that’s a hard situation, because you being CEO of the company becomes subjective the decision not to sell because you’re confident of what’s going on. And it’s not only the money, you’re thinking, like I’m selling it, I’m kind of saying goodbye to something that I’m part of.

Noa Eshed 20:46

Mine I built.

Ronen 20:48

Did you have that feeling? Or was it just like an economic thing?

Rand 20:51

Um, I think both of those. I would say, you know, what, in the HubSpot offer, I knew Brian and Dharmesh really well, I was excited to work with them. I thought very highly of their company. So no, I would say I would say it was mostly an economic decision at that point, right? Because I don’t think I don’t think I had a lot of non financial things holding me back from saying yes to that deal. I think it was mostly just, I think we’re worth more than this. And look, let’s hold on, you know, this is our first offer, let’s see what other offers we’re gonna get over the years. And we have this great company and this great growth rate. And, you know, I really like working here, let’s, let’s see how it goes. And then, of course, you know, you fast forward two years later, and the growth rate stalls, and I’m no longer CEO, and I feel like I can’t, you know, sort of influence and control the company and do the things that I think would lead the company to greater success and that the offer looks better and better in the rearview mirror.

Noa Eshed 21:45

But I have to say, I’m still not sure what the lesson here is.

Rand 21:49

I would say there’s a few right, one of the ones that I would certainly tell folks to think about is, if you sell your first company early, you have a long life to build many other companies. And by selling that first one, and, you know, making, it wouldn’t have been a few million dollars, it would have been a lot of money, you take a ton of risk off the table for yourself and your family, for your employees, for your employees, families, you get sort of all the accolades and awards in the in the press, and you know, investors will be interested in you next time. So there’s a, there’s a tremendous amount of positives that come with that. And you remove a ton of risk. I understand that there’s some people who, you know, have sold their first companies and then been frustrated and felt like – ah, this wasn’t the greatest fit, and maybe I should have kept going with it. I think that that regret is totally plausible. But it’s a very solvable regret, because you can start another one.

Ronen 22:47

Right, you always have the option…

Rand 22:48

You always have the option to start another one. And it’ll be, you’ve learned so much that first time right the second time around, it’ll be even easier, which is why in a second and third time entrepreneurs tend to have more successful outcomes than first time. And I think that the, the reverse is not true, there’s no way to sort of go back in time and take that offer, once you turn it down. That makes things really difficult. And many, many companies I know, that I’ve talked to over the years, and this could be because I’ve written about Moz’s situation, but you know, I talk to a lot of entrepreneurs who’ve had this, a similar thing happened to them. You know they found a company that was doing well, they turned down acquisition offers, they, you know, found that a few years later, things got much harder. And even if you’re making, you know, again, going back to our growth model, you can make a lot more money. I mean, Moz is making 10 times more than 10 times as much as it was in 2011. But I don’t think that even today, we could sell for what we could have back then. And certainly even if we did sell for that, you know, the employees and founders wouldn’t make nearly as much because the dilution over the years from investment has meant that we have to do much, much better to make the same amount of money.

Noa Eshed 23:59

I think it may be it also takes a lot of confidence. It’s ironic, but actually a lot of confidence to say yes to such an offer. Because it sort of means that you believe that you can actually succeed with a new company. And if you feel a bit of an imposter and that you just got lucky, then maybe it’s actually a good reason to sell and just get it over with and reduce the risk. But also if this is if your business becomes your life and what you mean, then sort of putting a stop to that becomes more than an economical question. And it becomes very scary,

Ronen 24:35

But Noa, but physically, it’s like if you think about it. Even if you’re an imposter, if you kind of imposturing your own business, at the end of the day, that’s even more dangerous, keeping that business. Like when you sell a business, you may not have maximized the profits. So I’m agreeing here, because you didn’t maximize profits, but you got momentum. So, you know, Google knows you are, you’ve done it before you know for X amount of people, you’ve played the game, you won the game, like now it’s you’re not going to, there’s going to be it’s like having it, we talked about cars in the beginning, define your cars. So you sold in 10 million and not 100 million. So the 100 million guys are gonna laugh at you. But in the 10 million space, you’re rockstars. So you got momentum backing you up, at least you got momentum backing up, when you have a company and you went in at the end, you may lose that momentum, you may they’ll just say – oh, that company that was really good, then and then. So I have to agree that definitely like, that’s a great lesson, because it’s not a it’s not a greedy, it’s just understand that if you’re young enough, you probably going to have a lot of opportunities, at least get that backlink that that momentum with you. And you can repeat it, or at least try to repeat it investments will be easier, you know?

Rand 25:48

Yeah, I think so. I think actually, I agree with both of you. I think that there’s there’s an emotional side to the you know, to feeling like an imposter. And to being overconfident, I think you have to have a lot of, you know, self awareness to be able to correctly process what’s going to make you feel good or bad in the long term, and to be able to accept things that you won’t be able to control in the future in either in either case. So this is, you know, there’s no, there’s no easy answer here. I think one of the best lessons, though, that that any entrepreneur can take away is that in this world where dollars are chasing, not dollars, not profitable businesses, not sort of, you know, good survivable businesses, but growth and growth alone, you should recognize that even at small revenue numbers, having a high growth rate is potentially your most exciting asset. And when you have a very high growth rate, when you get to a place with a very high growth rate, even if you’re small, that might be a great time to market and sell your business, right to think about the percentage of growth rate year over year as being the marker rather than – hey, we are this big, or we’ve gotten to this point, now’s a good time, I think recognizing that growth rate is what’s valued, and that it’s harder and harder to achieve those numbers, as you grow, is something that everyone should consider.

Noa Eshed 27:10

I guess there’s no rule of thumb here, it’s a matter of understanding that you’ve hit some sort of momentum. And then just not to be greedy, maybe.

Rand 27:18

Yeah. And, and the other thing I might suggest to a lot of folks is, you don’t have to play this game. I think there’s a lot of like reaching out early in the call, there’s a lot of stuff that’s really dumb about playing the growth game and the, you know, seeking an exit game. You can build a small, slow growing business, but as so long as it’s profitable, and you own it, you can be taking money off the table every year and potentially, you know, be far more financially successful. I know plenty of entrepreneurs with consulting businesses, right with which the tech world looks down upon, and you know, derives it with pejoratives, like – oh, that’s a lifestyle business. And you know, how crappy. And they have made way more money. And a lot of them have had much more happiness and success and brought a lot more happiness and success to their team and employees as well. I think that the model that’s held up of, you know, oh, you know, scalable software entrepreneurs or product businesses, those are the markers of true success. I would reject that.

Noa Eshed 28:22

Yeah. And then also just leads to a situation where people just don’t know what they’re getting into at all. (Yeah), and then make wrong decisions.

Rand 28:30

It’s hard stuff. This is hard stuff to know, right? Because there’s not a it’s not like we take classes in – hey this is how all these different models function. And here’s what entrepreneurship looks like. And we don’t have a ton of coverage of anything except the, you know, the big fast growing venture raising tech firms. So it’s hard.

Noa Eshed 28:50

I think also for you, though, you’ve sort of managed, and I’m curious when in your life that happened to take ego out of the equation completely. And I know maybe rejecting the HubSpot offer sort of contradicts that, but maybe not. But just in general, it seems like you’re not letting ego affect your decisions, and you’re making it your business to be transparent about the uncomfortable in weaknesses that you have. And just wondering, how did you evolve into that? Or was that something that you always made sure to take out of the equation?

Rand 29:23

No. Okay, I think I’m gonna, I think I’m going to disagree strongly. I think I am very ego driven. I think I have a huge chip on my shoulder, about, you know, my experience at Moz. And I feel like I have to prove myself to, I don’t know, to whom, to the world, to me, maybe to meet most of all, that I can, you know, successfully build another company that I can scale it that I know how to build a great software firm that you know, some people at Moz maybe made mistakes in it not listening to me. Those kinds of things, right, so that those are very ego driven decisions. And a lot of that is the driving force behind why I’m building SparkToro and how I’m building it. And, you know, the fact that the investment talks that I used to raise basically say that my investors can’t remove me as CEO. And yeah, so there’s…

Noa Eshed 30:16

That’s not ego driven.

Rand 30:16

I will say… Yeah, I think it’s, I think it’s a self aware ego. And maybe that’s the difference.

Noa Eshed 30:24

Maybe we’re not defining ego the same, because I think ego is mostly driven by being very protective of your weaknesses. And just by defending yourself and sort of playing, you know, the big shot. And I think you have a lot of reasons to, you know, walk around with that attitude. And yet, it seems like you’ve really made it a mission of yours, to not do that, and, and to actually show people what it looks like behind the scenes for real in Silicon Valley. And just in general, for a manager leading a company, that sounds like, you know, the top of success almost. So that doesn’t sound very ego driven to me.

Rand 31:10

Well I appreciate that. Thank you. That’s a very kind compliment. And I think that certainly investment in self awareness, right, understanding your own psychology and what makes you happy and unhappy, and why you make logical or illogical decisions when you do, knowing the things that can sort of get to you. I think those are, yeah, those are powerful investments that people can make and should make. Certainly they’ve been some of the best ones that I’ve made. I think I talked about that a little bit in Lost and Founder.

Noa Eshed 31:38

Yeah, but it’s very vulnerable.

Rand 31:40

Yes. So that I think that vulnerability is highly correlated with ability to improve oneself awareness and one’s happiness. And it feels very scary, but it’s, in fact, incredibly uplifting and freeing. And I would, I would encourage more people to be more vulnerable. And I would certainly, I would also encourage anyone who sees vulnerability in others, especially in people around them not to take advantage of that and criticize it and use it to, you know, sort of bring that person down, but instead recognize and uplift them, and tell them – wow, that that was really vulnerable, and I’m so proud of you. And I want to encourage that and help you. And that’s awesome to see. I think that you know, much like transparency is getting more and more valued in companies and people over the last decade or two. I think vulnerability is a next thing that we should try to embrace.

Noa Eshed 32:38

I agree, but it just seems like especially in the business world, it’s just quite the risk, just to be yourself along with your weaknesses.

Rand 32:47

Yeah. Yeah, I agree with you. I think there’s, there’s risk, there’s also great reward. And maybe that’s, that’s, that’s how a lot of things work in this world.

Noa Eshed 32:56

Yeah, for sure. I think that your book would be something that can really empower people, especially when they encounter all these situations where they would sort of feel alone and that they’re the only ones going through that. And then reading your book, I think people can understand that it’s just a very, very natural part of doing business.

Rand 33:15

Yeah, I certainly hope so.

Ronen 33:17

And tell us about the new venture, your you talked a little bit about how you’re trying to implement all your lessons into new business. Like, how is that working out? And like, what what do you suppose is gonna be the biggest difference?

Rand 33:31

Gosh, I mean, it’s very early stages, we’re only six months in, and we, you know, we don’t have a product yet. We’re still in sort of the r&d phase. But so far, the business has felt very, very charmed, you know, we’re keeping it extremely small. Just just two of us, the two founders, Casey and myself. We are, we’ve done a little bit of contracting with some folks which has been great. But we are managing to being, you know, to stay as low burn as we possibly can, and hoping to give ourselves a long runway to figure out, you know, the space that we’re tackling and the market and the customers and the product.

Noa Eshed 34:14

Are you doing at grassroots, or did you get an investment for it?

Rand 34:17

We did, yep, we raised $1.3 million, we actually open sourced our investment documents, because they’re very unusual. So I, I opted out of the sort of classic structure and said – hey, I want to build a business that’s going to be profitable, that can be around for a long time, that can reward its investors and its founders, not just through an exit, but through, you know, distributions on annual profits. And so we remained an LLC, which is which is quite unusual. We have a an unusual payback structure for our investors where we sort of, you know, cap our salaries until our investors are paid back 1x their investments, so a number of, a number of unique twists on how to make it work. But it was, yeah, interesting enough to investors, we raise money from about 35 people, all individuals, and we’re gonna use that investment to basically be able to mostly pay ourselves in our, on our health care for the first year or two. And then if we find great growth opportunities, we’ll we’ll probably invest in those slowly. But taking a very conservative approach, not purely growth focused, but also profit focused.

Noa Eshed 35:30

And there’s also not one company now that that is flexing or taking control from you in any way, because it’s just seperate people who are invested in this.

Rand 35:40

Yeah, that’s right. So we don’t have a formal board of directors in this model. And we don’t have any institutional investors, I strongly suspect we won’t raise institutional money. I don’t want to rule it out entirely, you know, who knows, maybe this business becomes, you know, huge, and it really needs 10s of millions of dollars in investment, and then we might have those conversations, but I strongly doubt that. Yeah, the goal is make this product exist, I think that we were both excited about the concept behind it and sort of frustrated that it didn’t already exist and felt like there was an opportunity. And so we wanted to, we wanted to chase it down, but not with the pressure of having to be, you know, $100 million in revenue, or we’re useless. And that, that I think is often the case in, in venture land.

Noa Eshed 36:25

Do you want to tell us what the company is?

Rand 36:28

Sure. Yeah. So the company is called SparkToro. And essentially, what we are trying to build is a search engine for sources of influence, meaning that if you want to know, what do chefs in Los Angeles pay attention to, so that you can market to them and advertise to them and, and reach them through places where they’re paying attention, you can go, you know, plug that into our tool, and we will show you the you know, the podcasts and the websites that they read, and the YouTube channels they subscribe to and people that they follow on social networks, like Twitter, and Instagram and LinkedIn. And, you know, the media sources, they pay attention, to the events that they go to. So that you can say – okay, if we want to reach chefs in LA, we should, you know, try and speak at this event and get a booth at that one. And, you know, sponsor this podcast and…

Noa Eshed 37:22

So really understand target audiences in depth.

Rand 37:24

Yeah, it’s about audience intelligence is what we’re calling the field. I’m not sure that that that field has a particular term. So…

Noa Eshed 37:31

Maybe you’ll coin it.

Rand 37:33

We’ll see, fingers crossed.

Noa Eshed 37:34

And this is a very much like, Moz for a niche audience then. This is not mass market, sort of solution.

Rand 37:40

Yeah, I think it’s very similar to Moz. And Moz was software for SEO professionals. I think, SparkToro is going to be marketing software for marketers who do outreach and targeting of all kinds.

Noa Eshed 37:54

Yeah, okay. Well, you’ve definitely got a lot of tools acquired a lot of tools during the years that to make that happen. Like, how do you, for example, approach hiring now, do you approach it differently?

Rand 38:05

Right now, we’re not approaching it at all, our plan is, basically wait until we have the revenue to sort of justify to ourselves, hey, we can see that there’s real customer demand here. And there’s growth happening. So we know that, you know, we can’t handle all of the work. Now let’s bring in somebody, as opposed to what I think happens very often, which is you raise some money, you build a team, and then your burn rate is very high, and you keep your fingers crossed, that you can, you know, make some money to support that team. Our plan is sort of the opposite.

Noa Eshed 38:35

Yeah. And also, when people do that, then they’re really not maxing out the potential of the current people on board.

Rand 38:41

Yeah, I guess there’s a little bit of that I, I’m not a big fan of, you know, crazy long hours and sort of working yourself to the bone. I think that that’s occasionally required. And certainly sometimes in my career, I’ve been there, but I like functioning on a lot of sleep. I like to, yeah, I like to make sure that I have time for friends and for Geraldine my wife and being able to travel and all those things, too. So in a lot of ways, I think, you know, Casey and I are building what venture capitalists often pejoratively call a lifestyle business, but one that I fully expect will grow and I think has the potential to be much more successful than many, if not most venture investments.

Ronen 39:25

What do you think? If you had to pick one, what would be your superpower?

Rand 39:30

Email!

Noa Eshed 39:35

SEO.

Rand 39:35

No, I yeah, I mean, I think I was I think I was pretty good at SEO. I have a relatively good skill in sort of people empathy, being able to put myself in their shoes and thinking about what they would want and how they would respond to something and act but yeah, for a long time, I think a lot of people who know me have said, you know, Rand’s superpower is email. That guy can get through 50 emails in, you know, an hour and they’ll all be well responded to and because you can sort of quickly process what’s interesting and what’s not and send good, cogent, thoughtful, kind responses that people respond well to and reach out to a lot of people that way. So I yeah, I love, I love my email.

Ronen 40:19

And on the kryptonite side?

Rand 40:22

Kryptonite? Heavy process, I think, I think when things are a process heavy, there’s lots of meetings, lots of approvals, lots of sort of political processes to get through in order to get things done. As opposed to a very relatively speaking dictatorial system, right? You do this, you do this, I’ll do this, we’ll all get it done by this day. I work much better in process free or process light companies than process heavy ones.

Ronen 40:52

Right. Is there a life hack to not making organization (heavy), heavy, and like I meaning with six people, it’s logical, but like 30, 40 people company and over being non structured, is I think a life hack for that?

Rand 41:06

You’re correct in that. Naturally, as companies get bigger, more process gets introduced. And that, you know, that creates this, those sorts of environments. But I think there are absolutely things you can do to mitigate it. One is to give a lot of freedom in terms of how processes are accomplished across an organization to individual teams. So for every team of whatever it is 6 to 10 people who’s working on something, you can tell them – hey, you define your process, we’re not gonna force you to use, you know, JIRA, or force you to use Google Docs or force you to use you 6 people agree on what works best for you. So long as you, you know, hit these things, which are requirements, we’re fine with it, and we don’t, you know, we’re not going to demand and require a ton of like, oversight into everything you are doing and how you got to the end goal, and, and all that kind of stuff, right? Here’s the, here’s the general requirements around whatever security compliance and legal compliance and, and what the customer needs. The rest, you go take care of. Right, we trust you. And I think that that sort of light touch from management can be very empowering for for certain people, for certain, for other people that they hate it, right? They, they like that big sort of bureaucratic structure where everything is well known and well documented, it’s all the same. And if I move to any team in the company, where everybody does things the same way, you know, there’s consistency of process. And it might be a heavy process, but at least it’s, you know, easy to understand and easy to migrate around. So there’s trade offs.

Ronen 42:40

Right. I heard a metaphor that talked about that. And that, it’s like the difference between a farmer and the hunter. Like, you know, the farmer can, can put a seed and just wait for it to grow. And there’s other people in organizations that are hunters, that one time you come home with the cheetah, and one time you have no food at all. So it’s kind of like the creative and non creative people.

Rand 43:03

Hmm, interesting. Interesting. So wait, is the hunter the process light? And the farmer? Is the process heavy?

Ronen 43:09

Yeah, the hunters process light, because he, the idea is he goes out at home with not knowing exactly the structure or how he’s going to catch when he catches or, or how is this going to be. And the farmer actually asked to have a methodical ruling of the day to have that, you know, strawberry field be perfect. And, you know, just keep on the seasons growing and everything. So there’s a lot of thinking before of the whole process.

Noa Eshed 43:35

But how can you like when you’re hiring? Who is, who is that hunter?

Rand 43:38

Oh, I think asking people, things that they really enjoyed and, and didn’t enjoy in previous jobs, looking at where they worked, and where they thrived. And didn’t. Those are really good markers for that. Right? So if someone says to me, you know – hey, I spent three years at Amazon, before that I was at a startup, I loved my startup environment. But you know, at Amazon, I got into these political battles. And that was really hard for me. And that’s one of the reasons I’m leaving, I sort of go – okay, I know what kind of person that is, right? I know what sort of team and structure they’re looking for, versus, you know, versus sort of the reverse of that, where well, things were very uncertain in the startup. And there was, you know, a lot of fear going around, and we had, you know, everybody was like chickens running around without their heads off. I didn’t know what I was, what what success looked like. It wasn’t well defined by my manager. And then I, you know, spent a few years at whatever it is Google right. And I really enjoy that environment and sort of the security there freed me to be able to do what I do best and okay, that’s, that’s another kind of person, and neither of those are negative. I think both are totally reasonable. It’s just what’s a good fit for your company. And your structure.

Noa Eshed 44:50

Yeah, it’s very difficult, I think to understand, A what you have understood, that is a good fit for your company. And then to actually identify that, especially when recruiting, understanding if a person is a good cultural fit.

Rand 45:06

Agreed.

Noa Eshed 45:07

I think it’s easier to understand if a person is a good fit with respect to their skills. But when it comes to an actual, true cultural fit, it’s really a room for a lot of misunderstandings and mistakes and a lot of suffering along the road.

Rand 45:22

Yeah, I think we’re, I totally agree, I think we’re much better trained in sort of the business world and society to value and recognize and judge skill in others and not recognize and judge and assess culture fit. And some of that is, we don’t even recognize what our own culture is. And so it is tough for us to broadcast that to someone else. And it’s tough for us to hire for, right culture fits.

Noa Eshed 45:49

The sort of thing that when you hire a person who’s a good cultural fit, it’s very clear, like you feel it. But it’s very difficult, at least I find it difficult to sort of define it and say, this is what makes that person a good fit, and that person less of it.

Rand 46:05

Yeah, I think part of this is just a time thing, right? Over time you recognize, you know, you hire people, you let them go. And you recognize, hey, these are people who work really well in our team, and what are the shared characteristics that they have, right? They have, whatever a strong belief in autonomy, for example, they’re good at committing to dates and getting things done on time, right. So they’re, they’re very good at estimates, even without process, which I think is, you know, that’s a challenging thing. But some people are really good at it, others are much less good at it. And I think that, you know, you can identify those skills and traits over time, and then start to hire for them specifically. But certainly in the early days, like a lot of things you’re muddling through, right, you’re gonna make mistakes, that’s okay. It’s not their fault. It’s not your fault. And I think having those conversations too right. The first few people that we hire for SparkToro, I am absolutely going to have the conversation of – hey, we’re really excited to bring you aboard. You’re our first employee, we don’t you know, we don’t know a lot about how this company is going to grow and what work is going to look like. And so we should give each other a lot of room and forgiveness for mistakes that we will undoubtedly make. And if in six months, this isn’t working out for you, or it’s not working out for us, we should just be honest with each other. We shouldn’t hold each other to to blame. Right? We shouldn’t be angry. We should just accept that. That is part of it. And if we’re comfortable with that, great. Let’s let’s make the hire and if you’re not comfortable with that, then it is probably not a good fit.

Noa Eshed 47:29

Yeah, in the first place. Okay, great. This is, this is really great. This was super interesting. We wish you a lot of luck with SparkToro. With the book it seems like it’s already going pretty well, right.

Rand 47:41

Yeah, it is. gotten some really nice feedback. Our Business Insider just had a sort of list of the highest rated books of business books of 2018. And think Lost and Founder was tied for first place. It was kind of exciting.

Ronen 47:56

Yeah, no, I totally get that. Like I have to on a personal note, they got you know, it is a podcast. So I don’t want to find, find myself being not as biased. But the book is genuinely an inspiration. Because it’s like not having a model of building a book, just writing down what you think. And I think people appreciate it at least we appreciate it a lot. And that’s a source of information. Because at the end of the day, you read books that have great theories, but you also would want to hear just a perspective that’s fresh and filtered. And so that’s how the feeling you get out of it. And, and we thank you for that. And we really, we love that book and share it to anybody that wants to get into business.

Noa Eshed 48:39

Anybody listening should definitely read that book.

Rand 48:42

Thank you so much. I’m thrilled to hear that it resonated. That’s wonderful.

Noa Eshed 48:45

100% did. So a lot of luck and thank you.

Rand 48:50

Yeah, my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

In this episode, we’re excited to be joined by Donna Griffit, a world-renowned... Read more

E70 - Roy Gottlieb (Co-founder & CEO of a VC backed stealth cybersecurity startup) Read more

In this episode, we speak with Liron Azrielant, a Founding Managing Partner at... Read more

In this episode, we speak with Asaf Yanai, a visionary entrepreneur and the... Read more

In this special wartime episode, we speak with Asaf Shamly, a visionary entrepreneur... Read more

In this special episode, we’re pleased to have Andy Ram as our guest. ... Read more